Manga Fandom in Australia by Queenie Chan

To read this essay in continuous scrolling image format please click here.

(Not recommended for blind or vision impared readers. Accessible text and image version below).

The concept of ‘Australian manga’ is one that few people are aware of, even if they are reasonably well-informed about the large, global subculture behind it. For many who live acclimatised to the hegemonic, Western (read: American) cultural landscape that dominates this country, it’s inevitable that they are slow to embrace Australian manga’s inclusion in the history of Australian comics.

My own journey with it, however, began not in Australia but in my birthplace of Hong Kong. Growing up in Hong Kong in the 80s, reading manga was just a part of my childhood.

My experience of 80s Australia was that of a sleepy surburbia that was (literally) a million miles away from the bustle of a big city like Hong Kong. Television largely consisted of surf-obsessed lily-white cast members who didn’t match the broad array of skin tones on display at my primary school. One time, a classmate secretly confessed to me that she was ashamed of being Chinese—a specific, local-born form of identity crisis that I, a child migrant from a well-off family, just didn’t understand.

Australian popular culture held little appeal to me, and had no reason to either. The sheer lack of entertainment choices eventually led me to Sydney’s Chinatown, and to a handful of Chinese-owned newsagencies on Sussex Street that unexpectedly sold Chinese-language manga.Every week, much of the pocket money I had would go straight towards buying these manga, and my bookshelf would expand. Along with my family’s yearly trips back to Hong Kong, this was what kept the connection to my birthplace alive.

Keeping my ties to Hong Kong was less a luxury than a necessity. After all, reminders of my own foreignness were constant, and near impossible to escape.

The 80s morphed into the 90s, with neither decade holding much interest for me besides the rise of video gaming, and the growing international presence of Japanese anime. Although it had been a global phenomenon since the sixties, with the sucess of Astroboy, it finally began to gain a more noticeable profile on Australian television.

Aside from Evangelion, the appearance of Ghost in the Shell on SBS at the time seemed to give Japanese visual pop culture a veneer of social acceptability. It was perhaps no surprise that these two shows were popular—both were from the hard science-fiction genres, and early anime fandom seemed to have a strong connection to science fiction and tech communities who gravitated towards anime due to how different it was to mainstream fare.

While I wasn’t a science-fiction fan, it was an appetite for difference I could relate to. Apart from manga, I was also heavily involved with computers as a teenager, due to having a father who was an early adopter of trendy new toys. Since my first exposure to home computing was an IBM computer he bought in 1984, I quickly developed an interest in programming, which was spurred on by the video-gaming hobby I then developed.

A gamer girl in the burgeoning, tech-savvy video-gaming subculture of the 90s was unusual, but since it was an entertainment category in which Japanese influence reigned supreme and unquestioned at the time, participants were also a lot more accepting of manga-style artwork compared to mainstream society.

Gaming might have been a male-dominated space, but it was one that I felt comfortable in. My parents also encouraged me to develop my hobbies, so as a teen, I was able to engage in activities as diverse as building my own computers and drawing my own manga-style comics in imitation of my heroes. Unfortunately, I had few friends who read manga and therefore no one to show my efforts off to, but that was all about to change in an enormous and unforeseen way.

Comics artists are not known for being techies, but it’s hard to understate how strong a role the early internet played in connecting isolated fans of Japanese pop culture worldwide. As someone who got my first email address in high school (and had no one to email), it was a time in which almost 50% of online content seemed to be anime-related.

In those wild west days of the early internet, the web was refreshingly free from the presence and therefore trespasses of large corporations, advertisers, government surveillance, parents, social media giants, and even most humans on the planet. Yet, it was also bewilderingly full of students, hackers, and housewives who liked anime and wanted to share their obsession, some of which spilled over into the real world.

The UNSW Anime Club meetings seemed well-attended and rowdy events, but I rarely went since I was more interested in the online anime community. Going to university and discovering (white) people who had an interest in Asian pop culture was a revelation for me, but as a typical programmer who shunned human contact, I preferred the online cauldron of chaos to the humdrum of my university classes.

Not to say that there was nothing of interest going on in my Bachelor of Science in Information Systems degree. Being naturally inclined to spend all day in the computer labs, I encountered plenty of physics majors, computer science students, and hard-partying engineers who shared my hobby.

The recommendations came thick and fast. AltaVista sucks, have you heard of Google? You should use Kazaa, it’s better than Napster. Did you know that on #anime in mIRC, you can download fan-scanlations of manga? (That last statement is true, but you will also find yourself #51 in a queue of people who have nothing better to do on a Saturday night either.)

My university life became a blur of programming, drawing my own manga in my spare time, and pirating manga scanslations via dial-up modem—all activities done while bathing in the glow of a computer monitor. My discovery of GeoCities, a website that allowed users to create their own websites, gave me a flash of inspiration: what if I uploaded my manga to the internet? It turned out a lot of people had the same idea.

Perhaps it was inevitable that drawing manga would take over more and more of my life. By the time the dot-com bust came and went, I was submitting my work (online) to US publishers—and getting accepted and published. The urge to self-promote and reach out to readers then appeared, and I reconnected with some of my real-life university friends. This eventually lead me down a different rabbit hole compared to all my previous journeys—that is, the parallel universe of the anime convention circuit.

Early Sydney-based anime cons such as Animania and the later, more enduring SMASH! (which started at UNSW) seemed to me like extensions of the anime club meetings from university. They were full of loudly chattering people who knew—thanks to the internet—exactly what they wanted, and what they were looking for.

Featuring the usual constellation of anime/manga/gaming enthusiasts and joined by merchandisers, cosplayers, model collectors, and vocaloid concert-goers, the anime con circuit remains unique in how self-contained and impervious it is to outside cultural influences. Unlike more general pop culture conventions like Supanova and the more recent Oz Comic-Con, which are family-oriented events that try to cover all bases, the anime con circuit is made up of niche affairs that make little attempt to appeal to outsiders—and seem to do just fine.

At the time, I had already created a manga series called The Dreaming for US manga publisher TOKYOPOP, a feat that gave me the sometimes-moniker of ‘Australia’s first internationally published manga artist’. The Dreaming directly referenced Australian culture due to its Picnic at Hanging Rock influences, but to be clear, this wasn’t typical of the work then being produced by Australian manga artists.

A lack of institutionalised support, the means to publish and distribute, and a shortage of highly skilled artists meant that most of these efforts were not widely seen. There were several locally-produced anthologies of Australian manga such as Generation and Oztaku which were printed and sold at conventions, but it was telling that most such creators did not seem to know of, or seem interested in, aligning themselves with the wider Australian comics-creating community.

I personally didn’t encounter most creators of Australian comics until I started guesting at cons like Supanova and OzComic-Con in 2013. This was probably because it’s possible to be hermetically sealed in the anime con circuit and have all your entertainment needs met, whether it’s comics, films, video games, music, dance, or fancy dress.

In fact, my first impression was bewilderment that Australian comics even existed as a category, followed by the realisation that it was something either homegrown, or an outgrowth of the American indie comics movement. The more I learned about it, the more I realised that it sported a history that I, as a migrant, didn’t really feel connected to.

This age and gender gap was particularly striking, as it brought home the incredible influence the internet had—not just on the global flow of culture, but how it could create parallel realities among different groups of people, even when they were working in the same medium.

The communities are so different they may as well exist in separate realities. Everything is different—the everyday lingo, common cultural touchstones, inside jokes, preferred methods of interpersonal networking, tools and processes used to create art, famous personalities, sales and distribution networks, and so on.

This can mean that group conversations at Western comic conventions can feel baffling and alienating to me.

It’s not that the conversations of manga and anime fans or gamers are fully comprehensible to me either, though a portion of them will be. Fact is, while all people talk in encryptions that are a combination of historical context, their own personal experiences, and what aspect of a subculture they are drawn to, there are also generalities that most fans in a subculture will understand.

It is perhaps this underlying similarity between the structure of different subcultures that may be the sole commonality between all of them. However, once again, the influence of the internet can inject itself into all this, by instilling a kind of timelessness into perennial fan favourites.

For example, Dragon Ball Z may have been first published in the mid-80s, but its fanbase includes many younger kids who know full well how old it is. It is the on-going existence of its massive online fanbase that actually removes Dragon Ball Z from any real-world historical context, something helped by the manga’s own fantastical setting.

However, despite the internet’s power to unmoor cultural products from their original time of production, how it affects said product in the real world is still an open question.

Nostalgia is a powerful thing. Impressions that form in our early years tend to last a lifetime, but such things are also tied to the specific era in which one was so young and impressionable. The 70s and 80s might have been the heyday of superhero comics and their indie counterparts, but rare are the children who grew up in the 90s and beyond whose first exposure to comics was through the printed floppies that Marvel and DC produces. Instead, that younger generation’s concept of entertainment is ephemeral, be it the 0s and 1s of a video game, or the digitised fan-translated and pirated manga that can be found all over the internet. For these youngsters, superheroes are less comics than they are movies and the occasional MMO game.

One of the defining political debates I remember from the 90s was the question of our national identity. When then-Prime Minister Paul Keating announced that he saw Australia’s future in closer economic and cultural ties with Asia, he seemed to be envisioning a vague, distant future which sounded like a good idea to shuffle towards. Now, thirty years later and in a very different world, his vision seems less government policy than gravitational pull.

Things change, and attitudes change. World-altering events can happen in the blink of an eye, and upset the existing global order. An example would the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, which caused the comics industry on both sides of the Pacific to suffer crushing blows from a combination of closed comic shops, production delays, turbulence in the distribution chain, and a general collapse of consumer spending. In this day and age, a disparate community should come together, not only for comfort but also for survival into the future.

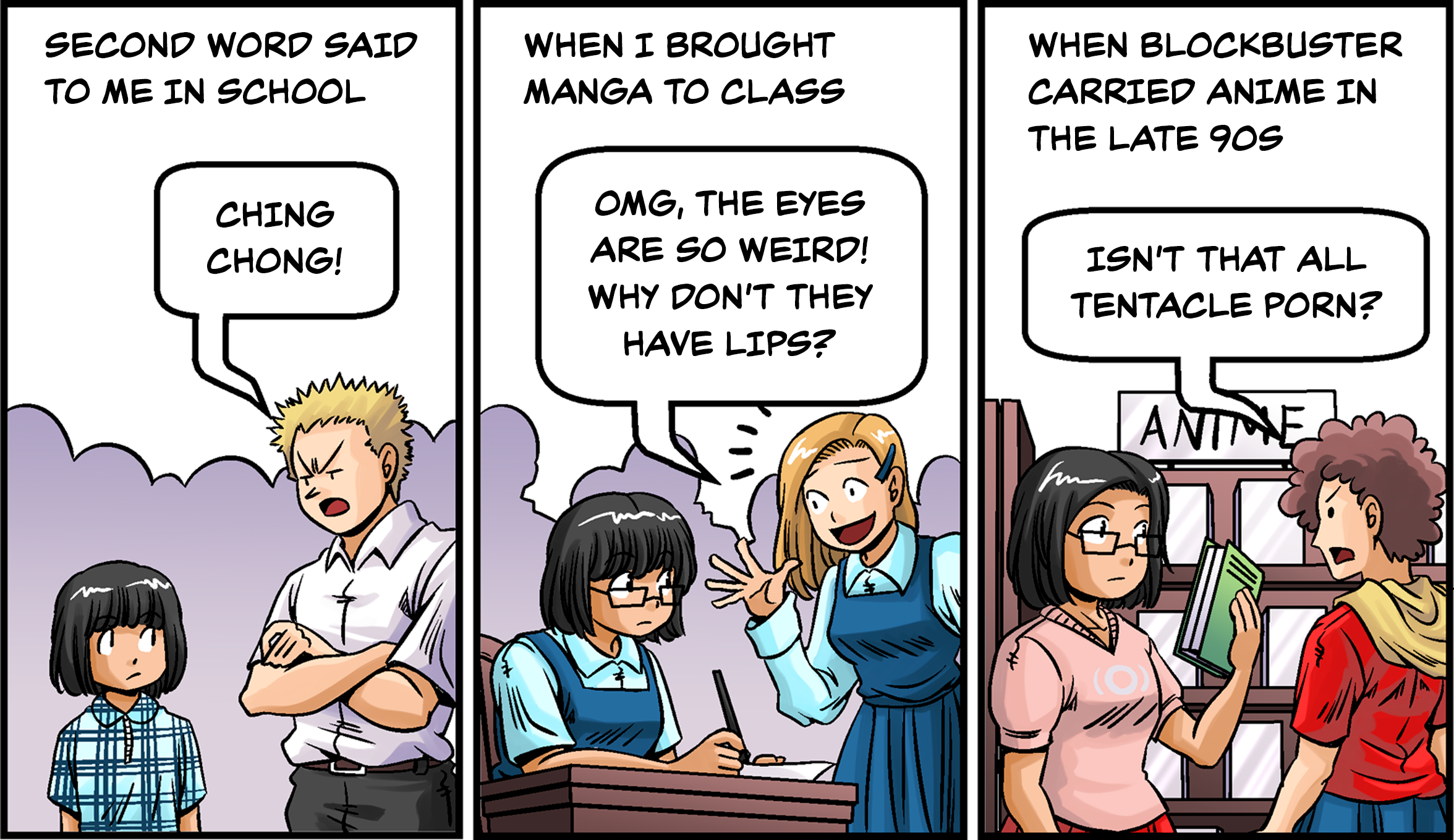

Yes, change does come slowly, but it’s recognisable when it does. In 2018, I created a comic for ABC National Radio that addressed my experiences as an Australian manga artist. The strip was widely shared on Twitter, but out of all the positive comments, it was one from a member of the Australian comics community that surprised me the most.

Well, that was unexpected. The fact that somebody had to explicitly make that statement seems to say a lot about the existing state of affairs, but it was a nice sentiment regardless. As tribes that rarely cross paths, an acknowledgement of the other’s existence is a good start to reconciliation. After all, even if it had to come decades late...

The views expressed in this essay are the author's own, and don't necessarily reflect the views or opinions of the Universities, Partner Organisations or other parties involved in the Australia Research Council project.

Queenie Chan

Author Bio

Queenie Chan was born in Hong Kong, and migrated to Australia when she was six years old. Her first published work was 'The Dreaming', a mystery-horror series for LA-based manga publisher TOKYOPOP, which has since been translated into multiple languages. She then collaborated on several graphic novels with best-selling author Dean Koontz for his ‘Odd Thomas’ series, as well as with author Kylie Chan for ‘Small Shen’. After that, she worked on several anthologies, and completed a fairytale inspired fantasy series called 'Fabled Kingdom'.

She is currently studying for a PhD about the intersection of comic and video games at Macquarie University, and creating a series of biographical young adult comics on famous historical queens called "Women Who Were Kings". Please visit queeniechan.com for more information.